I’m always interested in what people are reading. Recently, a friend told me her book club had just finished My Antonia (1918). She had suggested it, remembering how much she enjoyed Willa Cather’s novel when she was younger. And I wondered: Why don’t we read the classics more?

Probably many of us were introduced to them too early. I’ve never fully recovered from George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss in eighth grade. Such assigned works came with an implicit message that they were supposed to be “good for you,” making them the literary equivalent of asparagus, broccoli, and other largely inedible foods in the young person’s mind. I suspect we weren’t ready for some of the books. We hadn’t lived enough, hadn’t experienced enough to appreciate them. (Middlemarch. Definitely, Middlemarch.)

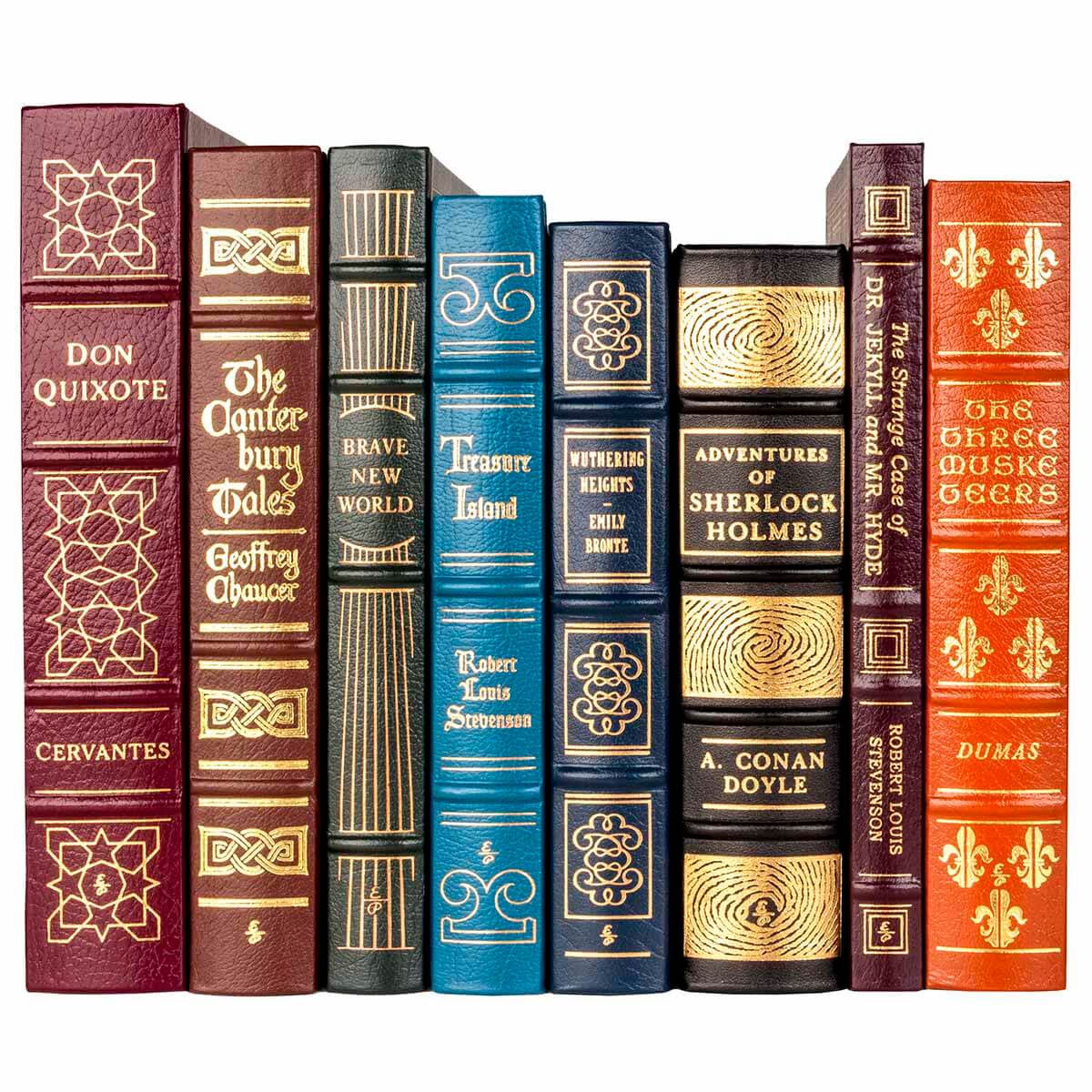

And yet, some persist in our memories, sentimental favorites—Treasure Island, Little Women, The Secret Garden, David Copperfield—like warm recollections of a childhood friendship.

Italo Calvino said, "A classic is a book that has never finished saying what it has to say." These are books that have stood the test of time. They speak to each new age, offering truths and insights into the human condition that continue to be relevant today. They are books that stay with us, long after we’ve finished them. In contrast, there is something ephemeral about contemporary fiction. Always has been—Fun activity for a rainy Sunday afternoon: Google the list of Pulitzer Prize-winning novels of the last hundred years. I’m betting you’ve never heard of most of them; very few are read today. And beware the book reviewer who proclaims some new novel “an instant classic.” Mmm, yeah, probably not.

Maybe it’s just me. After a summer of fun, frothy, easily forgettable beach reads, one craves something meatier. Like hungering for something more substantial after eating lots of cotton candy. In my novel, The Legacy of Emily Hargraves (yet to be declared a classic) the bibliophile Ashley recommends reading one classic each year. You don’t need to lead with the heavy hitters, Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment or Tolstoy’s War and Peace. Start with Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. You may appreciate her sly, wry social commentary that you missed in high school.

Or like my friend, re-read (and re-discover) a favorite from your childhood (Charlotte’s Web, Alice in Wonderland, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe) or from when you were a teen (The Hobbit, The Count of Monte Cristo, Great Expectations.) If you liked Dickens, try his unfinished novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood—I remember racing through that book to see how it doesn’t end—and then pick up Dan Simmons’ Drood (2009) which plays with the novel’s mysteries in the context of the great novelist’s final days.

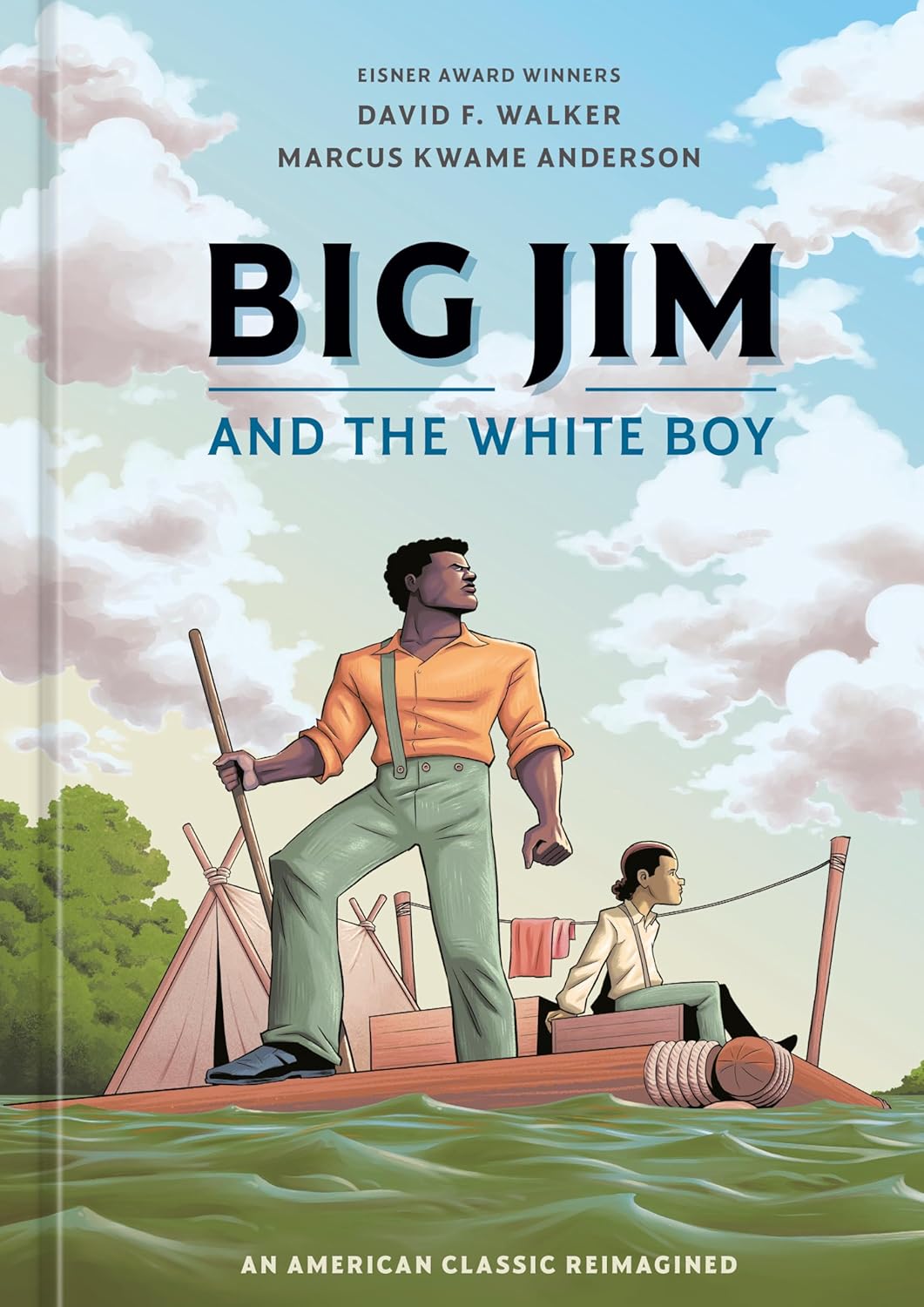

Or try Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, then read Percival Everett’s James (2024), which tells Twain’s classic tale from the viewpoint of Jim. Want something to steady and center you in these unsteady times? Try Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations. He was one of the great and few good Roman emperors, probably the closest humanity has come to a philosopher king. Feeling lusty? Try D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928). Somewhat tame by today’s standards, it was banned for obscenity and not published in the US until 1959.

Here’s an idea: Read classic works that were published one hundred years ago in 1925. For example, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, then watch Baz Luhrmann’s lush film adaptation with Leonardo DiCaprio; or read Mrs. Dalloway, following it up with The Hours (1998), Michael Cunningham’s creative riff on Virginia Woolf’s ground-breaking novel.

Some works are definitely challenging. Last year I tackled Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain (1924). It is one of those great masterpieces of Western literature that everyone should read before they die, or die trying, or maybe die from trying. Consider it a chance to practice your skim-reflex, and it’s still less habit forming than most over-the-counter sleep aids.

For next year, you could consider works published in 1926: Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, Franz Kafka’s The Castle (Kafka seems increasingly relevant these days) or maybe The Murder of Roger Ackroyd by Agatha Christie.

With each book, step into a different world and into a different age. You may need to adjust to a different pace, a different style of expression, a different sense of time—time is experienced differently when traveling in horse-drawn carriages than in cars. By doing this, you may also realize how many of today’s so-called historical TV dramas are really just modern sensibilities and attitudes dressed up in period costumes (I’m looking at you, “Bridgerton”!) Choose one classic and devote yourself to it, dig into it. Ask yourself: Why is this book considered a classic? Why have people continued to read it? What might it have to say about life in this 21st century?

Try it. It will be good for you.

This review first appeared in The Columbia River Reader (October 15, 2025.) Reprinted with permission.